The World Today for February 07, 2024

NEED TO KNOW

Skidding Off the Rails

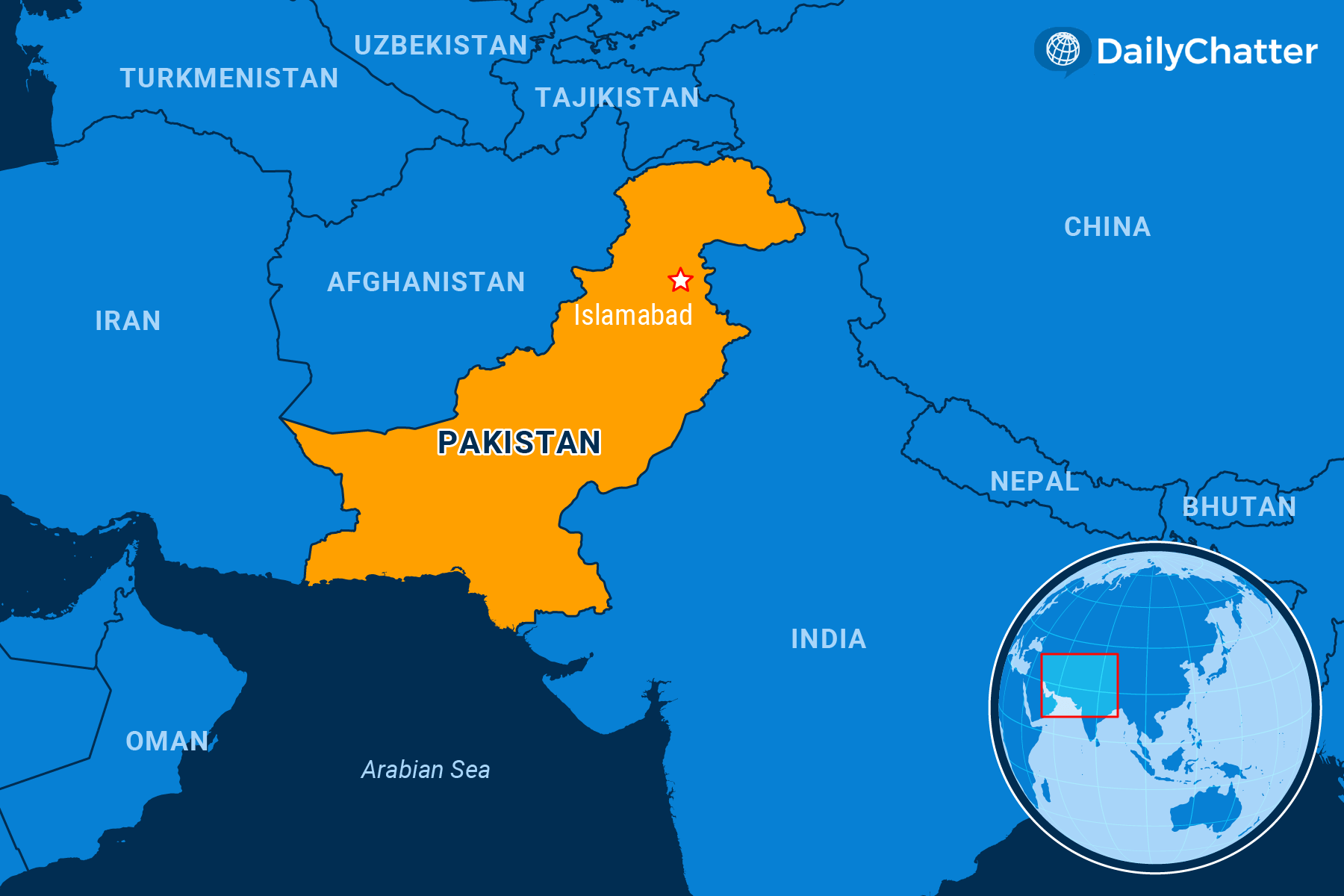

PAKISTAN

Late last month, courts in Pakistan in different rulings convicted ex-Prime Minister Imran Khan on charges of revealing state secrets and corruption, sentencing him to 14- and 12-year terms in prison around a week before Pakistani voters went to the polls to elect a new parliament. That followed charges of violating Pakistan’s marriage laws, for which he and his wife Bushra Bibi – also convicted of corruption – were sentenced just this Saturday to seven years in prison.

The ruling was yet another example of why the Brookings Institution described the South Asian country’s democracy as “badly damaged.”

Khan, an Oxford-educated former cricket star who left office in 2022, was already serving a three-year sentence on other corruption charges, reported the Associated Press. He faces 150 other cases, too. He is still a politically powerful political force in Pakistan, however, due to his personal popularity, his leadership of the Pakistan Tahreek-i-Insaf (PTI) political party, and his outspoken criticism of Pakistan’s political elites.

Khan and his allies – including those who have also faced criminal charges, wrote the Jurist – claim the government is targeting them to undercut the PTI’s chances at the polls.

“My party’s leaders, workers and social-media activists, along with supportive journalists, were abducted, incarcerated, tortured and pressured to leave the PTI,” Khan wrote in a prison letter published in the Economist. “Many of them remain locked up, with new charges being thrown at them every time the courts give them bail or set them free.”

Others have noted, for example, that Internet outages occurred, coincidentally, when the party was holding virtual rallies and other social media events, added Nikkei Asia. Election officials even barred the party from using its signature cricket bat symbol while electioneering on “technical grounds,” Al Jazeera noted.

The elites whom Khan threatens appear to be coalescing around another former prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz. He left office in 2017 due to corruption charges. He fled the country to avoid justice, but successfully appealed to have the charges overturned.

His rehabilitation doesn’t necessarily lend credence to the vote, however, say analysts. Nawaz’s strength indicates how the military, rather than the electorate, is in firm control of Pakistan, argued Thompson Rivers University political scientist Saira Bano in the Conversation. Generals have played kingmaker in the country for its 76 years of independence. They supported Khan when Sharif attempted to broker more peaceful relations with India, Pakistan’s historic nemesis. Ousted either by the military or courts, Sharif has held the highest office three times. Incidentally, in 2018, Khan won while Sharif was in jail.

Then Khan sought to challenge their power. “Sharif, a person who faces serious credibility allegations due to unaccountable overseas wealth, is once again the darling of the establishment as a much-needed alternative to the disruptive populism of Khan,” the East Asia Forum explained.

In Pakistan, which faces an array of political, economic and military issues, no prime minister has ever managed to complete their five-year term in office. Maybe that’s because, as the Wall Street Journal noted, that’s “the political rollercoaster ride that is Pakistani politics.”

THE WORLD, BRIEFLY

The Gravity of Futility

HAITI

Hundreds of people protested across Haiti this week demanding the resignation of Prime Minister Ariel Henry, because of the years-long political and economic crises that have led to a devastating security situation, the Associated Press reported.

Banks, schools and government buildings closed across the Caribbean island, while demonstrators blocked main roads and paralyzed public transport.

Among those protesting were politicians and heavily armed agents from the state’s environmental department – the latter have come under government scrutiny following recent clashes with police in the country’s north, the newswire wrote separately.

Henry assumed power shortly after the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021. The ensuing power vacuum has resulted in the rise of violent gangs that have taken control of neighborhoods and terrorized locals, and halted the movement of goods and services.

As police struggle to fight off gangs, which control a large swathe of the capital, citizens have been living with a spate of killings, sexual violence and kidnappings, Reuters noted.

Around 300,000 people have been internally displaced because of skirmishes between police, vigilantes and criminal groups, according to Human Rights Watch.

The United Nations warned that more than 50 percent of Haiti’s population is facing starvation because the conflict is preventing food and aid from moving into the country.

The demonstrations are expected to end Wednesday, Feb. 7 which protesters have set as the deadline for Henry to step down.

This date holds historical significance, marking the departure of former autocrat Jean-Claude Duvalier in 1986 and the inauguration of Haiti’s first democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, in 1991.

No Way Out

THAILAND

Thailand’s state prosecutors said on Tuesday they were reopening an investigation into former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra’s alleged violation of a strict royal insult law, just weeks before he was expected to be released after serving a sentence for corruption, the Associated Press reported.

Thaksin was charged with criticizing the royal family in 2016 following remarks he had made about the Thai monarchy to journalists in Seoul, South Korea, the year before. However, since he was in self-imposed exile, the case was paused until he could respond to the charges.

The billionaire became prime minister in 2001, running on a populist agenda, and his popularity reportedly came to overshadow that of the royal family. He left the country in 2008 following his ousting in a military coup two years earlier.

He voluntarily returned last August and because of ill health began serving an eight-year sentence for corruption and abuse of power in a Bangkok police hospital. There, police served him notice of the royal defamation charges on Jan. 17. Thaksin faces up to 15 years in prison under Article 112 of the criminal code, one of the world’s strictest laws on lèse-majesté.

After King Maha Vajiralongkorn reduced his sentence to 12 months last year, Thaksin became eligible for parole and was widely expected to be freed later this month. That’s in doubt after the prosecutors’ announcement.

His return had coincided with a parliamentary deal with lawmakers linked to the royalist military that made his daughter’s Pheu Thai party – the successor to his own political movement – the leading force in Thailand’s government following last year’s general election.

The winning party, Move Forward, was forced into opposition after Pheu Thai canceled their pre-electoral alliance. The left-leaning Move Forward Party ran on an anti-establishment platform and proposed amendments to Article 112.

Still, Thailand’s Constitutional Court last week ruled that the proposal violated the constitution and was a move toward the “destruction of the democratic system of governance with the king as the head of state,” Reuters reported.

Though the verdict included no punishment for Move Forward, it set a precedent for future reviews of Article 112 and could lead to calls from royalists to dissolve the party.

Defiance on Trial

BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA

The trial of the president of Bosnia’s Serb-majority region began this week, a case involving a major dispute between the Bosnian Serb leader and the international envoy overseeing the country’s peace agreements, Radio Free Europe reported.

Milorad Dodik, president of the Republika Srpska, is accused of defying decisions by Christian Schmidt, the international peace envoy and High Representative to Bosnia-Herzegovina charged with overseeing the enforcement of the Dayton Agreement that ended the country’s bloody civil war in the 1990s.

The charges against Dodik stem from two laws he signed in June that allowed Republika Srpska to disregard decisions made by Schmidt and the country’s constitutional court, according to Agence France-Presse.

On July 1, Schmidt annulled both bills.

The trial is scheduled to reconvene early next month, with the prosecution set to present evidence against the Bosnian Serb leader.

If found guilty, Dodik could face up to five years in prison and a ban on holding office.

He has dismissed the case as “a purely political process,” adding that he will not recognize the court’s verdict. His defense team contended that the evidence against him “isn’t based on facts.”

Dodik, a close ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, has refused to recognize Schmidt’s authority after Russia and China dropped their support for the position. He has frequently stoked ethnic tensions in the ethnically diverse nation and threatened to split Republika Srpska from the rest of the country.

Bosnia-Herzegovina operates under a complex administrative framework made up of two entities, a Bosniak-Croat federation and Republika Srpska, both overseen by a civilian high representative with substantial authority.

DISCOVERIES

Deadly Spells

A new study found that three pandemics in the Roman Empire aligned with periods of abnormally cold and dry weather, indicating a potential link between climate change and Rome’s decline, New Scientist reported.

Researcher Kyle Harper and his team analyzed sediment core data from the Adriatic Sea to reconstruct the climate of southern Italy from 200 BCE to 600 CE.

They explained that the Roman Empire thrived during a “Roman climate optimum” of warm and wet weather until around 130 CE, when temperatures dropped and droughts became more frequent.

The Antonine Plague in 165-180 CE and the Plague of Cyprian in 251-266 CE were marked with especially cold periods, contributing to the empire’s instability. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, a cold period marked by the Plague of Justinian in the 540s affected the Eastern Roman Empire.

While signs of cold spells were previously recorded in tree rings in the northern Alps, the recent analysis of the sediment core showed a decline in warm-water plankton species and species dependent on river-deposited nutrients – indicating aridity.

The researchers added that these cold and dry spells further disrupted harvests, weakened immune systems, and facilitated disease spread through migration and conflict.

While this research sheds light on climate patterns in Roman Italy, other researchers cautioned against attributing Rome’s downfall solely to climate change and pandemics, highlighting the complexity of historical events.

Even so, Harper emphasized that the study helps us understand the impact of climate change in antiquity and the significant strain that even slight temperature changes can impose on human civilizations.

“It gives your perspective to understand that two to three degrees (Celsius, or 3.6-5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) of change is absolutely enormous and puts tremendous strain on human societies,” he said.

Thank you for reading or listening to GlobalPost. If you’re not already a subscriber, you can become one by going to globalpost.com/subscribe/.

Not already a subscriber?

If you would like to receive DailyChatter directly to your inbox each morning, subscribe below with a free two-week trial.

Support journalism that’s independent, non-partisan, and fair.

If you are a student or faculty with a valid school email, you can sign up for a FREE student subscription or faculty subscription.

Questions? Write to us at [email protected].

Thank you for visiting, DailyChatter, the only daily newsletter focused exclusively on world events. We hope you enjoy reading (or listening to) this edition.

Thank you for visiting, DailyChatter, the only daily newsletter focused exclusively on world events. We hope you enjoy reading (or listening to) this edition.